AMES, Iowa – Growing populations and shrinking agricultural resources are among the most important challenges fac ing food production. To meet projected increases in global demand for food, feed and fiber, experts say progress is needed to accelerate genetic improvement of crops.

ing food production. To meet projected increases in global demand for food, feed and fiber, experts say progress is needed to accelerate genetic improvement of crops.

The USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture has awarded $649,443 for a three-year grant led by Siddique I. Aboobucker, research scientist in agronomy at Iowa State University, working with Thomas Lübberstedt, Frey Chair in Agronomy and director of the Raymond F. Baker Center for Plant Breeding. Their project will investigate genetic mechanisms that could be used to improve doubled haploid processes to create pure genetic lines for breeding corn and, eventually, other crops.

Use of DH method is one of the basic technologies underpinning modern corn breeding. It can speed up inbred line development by reducing the number of generations from seven in traditional breeding to two generations in DH breeding, according to Aboobucker.

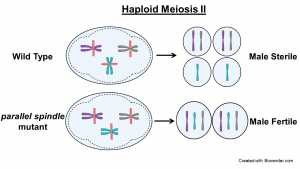

However, DH technology has significant challenges. It requires creation of haploid plants that carry only a single copy of the genome. Resulting haploid male flowers are usually sterile. Overcoming this problem has required exposing the seedlings to the toxic chemical colchicine in a labor-intensive and costly process that spurs genome doubling and returns fertility to haploid male flowers.

In earlier work, Aboobucker and colleagues demonstrated that exploiting mutations which modify the positioning of the spindle mechanism during the plant reproductive phase known as meiosis can restore male fertility of haploid plants. Aboobucker’s new project will build on this work by advancing identification and manipulation of genetic mutations that could more easily restore haploid male fertility in maize while avoiding the need for chemicals.

“The genetic mechanisms I’m exploring have great potential to make the technology for inbred line creation in maize more efficient and more widely available,” Aboobucker said. “As the same genes are also conserved in a number of other plant species, the research opens the possibility to apply the results to other crops in the future.”